Brugada syndrome: causes, symptoms, risks, treatment

Brugada Syndrome is a genetic disease characterized by disturbances in the electrical activity of the heart, in the absence of evident structural alterations in the myocardium.

Brugada Syndrome was first described by Italian authors in 1988, although the electrocardiographic findings characteristic of the disease were already evident in 1953 to Osher and Wolff, who detected dynamic abnormalities on the ECG that simulated a myocardial infarction in a subject. healthy male.

This syndrome is now known by reference to the name of the Brugada brothers, who described it in detail in 1992.

Some patients inherit the disorder from their parents while others, on the other hand, develop it between the ages of 30 and 40 in a completely inexplicable way.

Affected patients are more prone to developing malignant ventricular arrhythmias and are considered at risk of sudden death.

In most cases, the diagnosis is made through the detection of characteristic changes visible on the electrocardiogram (such as a right bundle branch block and an elevation of the ST segment in the right precordial leads). These electrocardiographic findings can

- Vary over time,

- Show up inconsistently

- Or be accentuated

- From taking medications (mainly sodium channel blockers, beta-blockers, lithium, and tricyclic antidepressants )

- Or some physical conditions (such as fever).

- Since the disease may be familial, screening of relatives of affected patients is recommended to assess the risk of the disease.

- In some patients the Brugada syndrome is asymptomatic, however, in many cases, ventricular arrhythmias can generate especially at night and without correlation with physical exercise

- Palpitations,

- Syncope,

- Ventricular arrhythmias,

- Cardiac arrest (in severe cases).

In patients suffering from Brugada Syndrome, it is recommended to avoid the intake of drugs and exposure to events that may favor the occurrence of arrhythmic episodes; in subjects with previous cardiac arrest and in those in which an electrophysiological study has shown the possibility of malignant ventricular arrhythmias, the implantation of an automatic defibrillator is recommended, able to continuously monitor the heart rhythm and to intervene in case of life-threatening arrhythmias.

Since Brugada Syndrome does not have a definite clinical progression, it is possible that the patient has a low arrhythmic risk for life, but it is still necessary to monitor the disease frequently through scheduled cardiological visits and possibly evaluates other therapeutic options, such as the use of antiarrhythmic drugs, such as quinidine.

WHAT ARE CARDIAC ARRHYTHMIAS?

The electrical impulse at the base of cardiac conduction usually originates from a structure located in correspondence with the right atrium, the sino-atrial node, which, acting as the heart’s natural pacemaker, represents the dominant pathway that causes the impulse propagates from the atria until it reaches the ventricles, stimulating their contraction.

This process allows cardiac activity to take place with a “sinus rhythm”, which has a frequency between 60 and 100 beats per minute in conditions of rest.

There are mainly three alterations in this process and only one of these conditions is enough for an arrhythmia to arise:

Changes in the frequency and regularity of the heartbeat; we are talking about tachycardia when the beat is accelerated (over 100 beats per minute) or bradycardia when it is slower (under 60 beats per minute).

Variations of the dominant pathway, mainly represented by the sinoatrial node, are able to guarantee the “normality” of the heartbeat.

Impulse conduction and propagation disturbances of contraction with alterations in the heart rhythm.

CAUSES

The disease mainly affects populations of Asian origin and is more frequent in males between the ages of 30 and 40, especially if they have family history behind them.

In most cases, at the basis of this syndrome there is a genetic functional anomaly transmitted from parents to children with autosomal dominant inheritance; for the remainder of the patients, the origin of the disease, on the other hand, remains unknown or not better clarified.

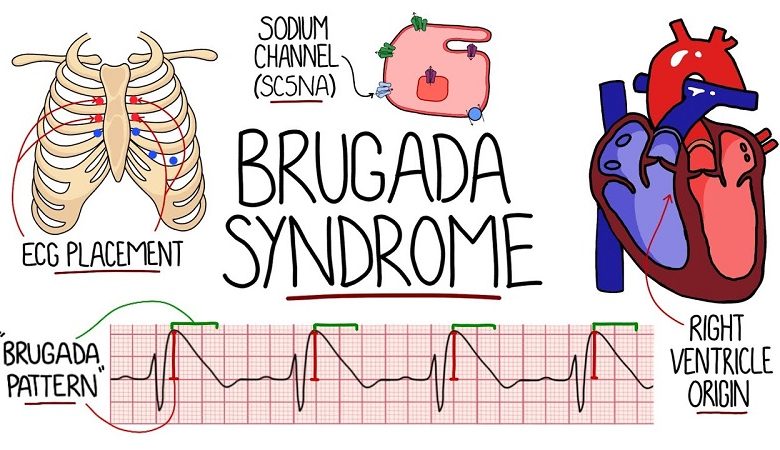

The genetic mutations mainly concern a gene located on chromosome 3, SCN5A, which produces channel-like proteins which, localizing in correspondence with the membrane of heart muscle cells, allow the passage of sodium ions, generating a real currency that is necessary for the transmission of electrical impulses and therefore for the contraction of the heart.

Patients with Brugada syndrome have a malfunction of these channels, which cannot guarantee an adequate heartbeat and can also lead to imbalances in cardiac electrical activity, increasing the risk of developing life-threatening arrhythmias.

Although the SCN5A mutation accounts for 18-30% of cases of Brugada Syndrome, other mutations affecting several genes have been highlighted as the research progresses, such as:

- Gpd1l: produces glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and, although it is not a membrane channel, it can modulate the ionic exchanges that take place within it;

- Cacna1 and cacnb2: produce membrane channels for calcium, the malfunction of which can alter the transmission of the contractile impulse in the heart;

- Scn1b and scn10a: two sodium channels, identified in 2013 and hypothetically involved in the genesis of the disease;

- Hey2: transcription factor, discovered in 2013 and with a role in the genesis of the disease still not well understood.

For cases of affected patients where Brugada Syndrome cannot be explained by an underlying genetic mutation, some reasons have been hypothesized for the incorrect transmission of electrical impulses in the heart, including:

- Drug use, mainly cocaine ;

- Hypertension ( high blood pressure );

- Angina pectoris ;

- Electrolyte imbalances (concerning the concentration of calcium, sodium, potassium ions in the blood);

- Taking certain medications (mainly sodium channel blockers, beta-blockers, lithium, and tricyclic antidepressants);

- Feverish states.

Patients with a family history of sudden death under the age of 45 should also be considered at increased risk of the disease.

SYMPTOMS

The disease presents with great clinical variability and the electrocardiogram of the affected patient can be subject to variations and appear pathological or substantially normal, even within the same day.

Patients may be asymptomatic or present:

Episodes of syncope (fainting), often not preceded by signs, are caused by the rapid and ineffective contraction of the ventricles which usually returns to normal after a few seconds; since the loss of consciousness is immediate, with no warning symptoms, patients are also at risk for trauma.

- Episodes of heart palpitations (the subjective sensation of heart palpitation), are often associated with malaise.

- Episodes of nocturnal enuresis (“bedwetting”), in the event, that arrhythmic syncope occurs during the night with sphincter release.

- Documented ventricular fibrillation.

- Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

- Agonic nocturnal breathing (“gasping” with a reduction in the frequency of respiratory acts).

Symptoms are mostly manifested at rest, during the night, or during the recovery phase from physical exercise, while adrenergic activation (in response to mental or physical stress) as well as physical exercise, are not contributing factors to arrhythmias. which manifest themselves in pathology.

COMPLICATIONS

Sudden cardiac death is the most tragic manifestation of the disease and usually occurs mostly in people between the ages of 25 and 50.

It is due to cardiac arrest caused by ventricular fibrillation; in this case, the lower chambers of the heart, the ventricles, contract very rapidly and irregularly, generating an invalid contraction that can stop cardiac activity, causing sudden death.

DIAGNOSIS

The first element that should lead to suspicion of Brugada Syndrome is the occurrence of fainting, cardiac arrest, or sudden death in a young person.

Through a correct diagnosis, it is possible to adopt therapeutic measures that allow to prevent the most tragic manifestations of the disease and to diagnose the disease in family members of patients affected by genetic mutations.

It is, therefore, necessary to consult an electrophysiologist (a cardiologist expert in electrical dysfunctions) who may use some tests, such as:

- 12-lead ECG : allows you to highlight three different disease patterns;

- Type 1: elevation of the st segment and elevation of the j point by at least 2 mm, negative t wave in v1-v3, with morphology similar to a right branch block.

- Type 2: elevation of the st segment of at least 1 mm and elevation of the j point of at least 2 mm, with positive or biphasic t wave. Type 2 can also be seen in otherwise healthy individuals.

- Type 3: elevation of the st segment of less than 1 mm and elevation of the j point of less than 1 mm, in the presence of a positive t wave. Type 3 is not uncommon in healthy individuals and is usually thought to be nonspecific if it does not spontaneously convert to type 1.

- Holter electrocardiogram: this allows the evaluation of the dynamic changes of the electrocardiographic trace and the possible presence of arrhythmias.

- Pharmacological tests: mainly based on the use of flecainide, an antiarrhythmic drug capable of bringing out the characteristic electrocardiographic profile in the presence of the disease.

- Genetic tests: are reserved for cases of patients with a family history of Brugada syndrome.

- Endocavitary electrophysiological study: it is proposed to test ventricular arrhythmic vulnerability in patients who are familiar with sudden cardiac death and is carried out through small probes that, from the femoral vein or subclavian, reach the heart under the guidance of x-rays.

- Echocardiogram: useful in differential diagnosis; in case of arrhythmias generated by structural damage of the heart it is in fact possible to exclude the presence of Brugada syndrome.

TREATMENT

The only treatment considered valid is the implantation of a defibrillator (ICD), which is housed in the left side of the chest and connected to the heart via leads; this device, which acts by delivering an electric shock when any arrhythmias are detected, will be able, if the discharge is successful, to restore the electrical activity of the heart to normal.

Since Brugada syndrome does not have a definite clinical progression, it is possible that the patient has a low arrhythmic risk for life, in this case, it will still be necessary to frequently monitor the disease through scheduled cardiological visits and possibly evaluate other therapeutic options, such as the use of antiarrhythmic drugs, such as quinidine.